INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS

I have in front of me a one page article in Beyond Today, an outreach periodical published by the United Church of God (UCG) (March-April 2017 issue) that discusses world news and prophecy. The author uses Brexit and a romantic quotation from Shakespeare of a “happy breed of men” who migrated to their island homeland to launch his short piece that leads the reader in the usual fashion to be offered a free copy of their booklet The United States and Britain in Bible Prophecy. This usual pattern is to provide the reader of some kind of contemporary geopolitical analysis and then shift the attention to a Biblical perspective:

“But there is a source of news, written in advance, that does not auger well for the immediate future. Trouble is in store because the related peoples of Britain , Europe, The United States and elsewhere have forgotten where they came from”. (Beyond Today – March-April 2017)

This would seem innocuous enough, but what follows is a misleading narrative historically and Biblically:

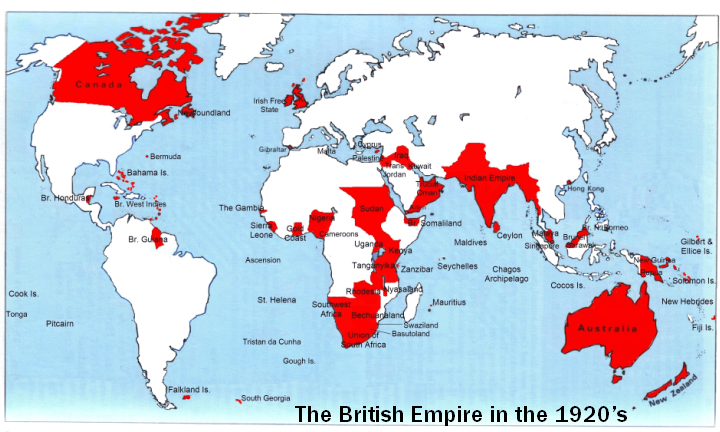

“They forget God at their peril. It is He who provided the Brits with this beautiful, bountiful homeland set in the silver sea. It is He who has overseen the course of their history, expanding their influence in the vast British Empire and Commonwealth, giving them favor in many lands–so that they and others might learn, eventually, that it is He who sits above the circle of the earth, with men like grasshoppers (Isaiah 40:22)

The happy breed of men who came to inherit the “scepter isle” came little by little over land and sea, over many centuries which makes for fascinating history since the ancient people from whom they derive were reputed to have been lost–having vanished from their original homeland following defeat and deportation”. (Beyond Today – March-April 2017)

Much of their readership are members of their business organization, and they are aware of what the author is alluding to. It is the claim that the northern tribes of Israel, primarily Ephraim and Manasseh once captive by the Assyrians, migrated, primarily under the name of Saxon, to what is now England, and through God’s assured providence became a dominant people in the world, having His blessings and favor.

The UCG and other organizations who have adopted this belief go through a fair bit of length in their literature to ensure there is an idea that God has expanded and blessed the people of the British Commonwealth, and ultimately the United States.

Within their own literature, the UCG quote the pontification of politicians as evidence of God’s approval of their wealth and how the wealth was obtained:

“It is hardly surprising that educated people of the day perceived the hand of God in the process. To them it seemed too obvious to ignore. For example, Lord Rosebery, a British foreign secretary (1886, 1892-1894) and prime minister (1894-1895), spoke in November 1900 to the students of Glasgow University about the British Empire:‘How marvelous it all is! Built not by saints and angels, but by the work of men’s hands … and yet not wholly human, for the most heedless and the most cynical must see the finger of the Divine. “Growing as trees grow, while others slept; fed by the faults of others as well as the character of our fathers; reaching with a ripple of a restless tide over tracts, and islands and continents, until our little Britain woke up to find herself the foster-mother of nations and the source of united empires. Do we not hail in this less the energy and fortune of a race than the supreme direction of the Almighty?’” – Page 82, United States and Britain in Bible Prophecy.

The booklet goes on to claim that

“The builders of the British Empire aspired to weld together a peaceful, productive domain ruling over a quarter of the world’s population. A great achievement of British administrators was the establishment and extension of law and order in Britain’s colonial and imperial territories around the globe. This alone brought untold blessings to the people of these territories.” –Page 83

The reality behind the growth of the British Empire is far different than the authors of this UCG publication would have us believe. The human cost to support the growth of this empire can be evaluated in terms of the deaths of tens of millions in its endeavors to obtain wealth and control people.

The source of this distortion of the historical record that has occurred does not happen by accident. It is the privilege of conquerors to tell stories that flatter their own past. All nations as they evolve over time attempt to distance themselves from their own atrocities. Most accounts present the British Empire as a great engine for diffusing liberty and civilization to the world.

Popular accounts continue to sell happy stories of the empire to the British public – always marketed as humanely generous revisionist accounts, but avoided are all the prevalent episodes of massacres, rebellions and atrocities. Particularly atrocious was the lucrative slave trade, endorsed by the crown, which afflicted and murdered millions of Africans between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. Britain’s expansionist agenda was in large part funded by the profits of slavery. The crimes against humanity committed by the British in its expansionist efforts are virtually unquantifiable.

Even well into the 20th century, the Empire continued its aggression at the expense of its colonies. In the book The Untold Story–The Concise History of the United States, the authors share the account of one of his sons, Elliott Roosevelt, during President Roosevelt’s meeting with Winston Churchill, where Elliott was in attendance. Churchill met with Roosevelt in Newfoundland to appeal for the US entry into the war. Elliott shared his father’s position:

“I think I speak as America’s President when I say that America won’t help England in this war simply so that she will be able to continue to ride roughshod over colonial peoples.”

The authors of the book comment:

“At the heart of Roosevelt’s vision was that political freedom meant economic freedom, which was in sharp contrast to the British Empire’s rationale that kept the colonies poor and dependent on London. Roosevelt’s global New Deal would create a financial credit system that would allow the colonies to develop.”

Roosevelt was determined to dismantle the colonial empire and its methods. Churchill knew that America’s terms in entering the war would be that Britain’s post war existence would not be the same.

Roosevelt saw colonialism as a threat to world peace. As recorded by his son Elliott in his book, As He Saw It, Roosevelt told his son,

“The colonial system means war. Exploit the resources of an India, a Burma, a Java; take all the wealth out of these countries, but never put anything back into them, things like education, decent standards of living, minimum health requirements–all you’re doing is storing up the kind of trouble that leads to war. All you’re doing is negating the value of any kind of organizational structure for peace before it begins.”

Roosevelt did not hold this position in isolation and was not alone in the knowledge of Britain’s exploitation of its colonies, particularly India. It is utterly absurd to read in Church organization literature how the decline of Britain’s Empire came about by God’s withholding of His blessings by the suggestion they have forgotten God at their own peril. This kind of literature and media programs that convey these ideas preys on the ignorance of its audience.

The high calling of the Church of God leaves it without excuse to adopt convenient ideas of history to serve its own agenda of increasing and retaining membership and advancing the British Israel doctrine. It is one thing to avoid the unpleasant realities of the past, but for a church organization to suggest “untold blessings to people of these territories” in the name of God is a serious matter, and they do so at their own peril.

The following pages feature the introduction of a recent book by historian Richard Gott – Britain’s Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt. Shepherd’s voice Magazine has obtained the rights to reproduce the introduction of the book, which this writer feels captures in part the historical narrative that the proliferators of British Israelism, or Anglo Israelism, would like us to ignore, and they themselves choose to willfully ignore.

In the pages of the book, Gott, as few have done before, demonstrates that violence was a central, constant and pervasive part of the making and keeping of the British Empire. We hope that our readers can exercise our individual responsibilities to prove all things, and to hold fast that which is good (1 Thessalonians 5:21).

May the Lord God, the Head of the Church, be found righteous in His judgement of it. As Paul said it well “…let God be true, and every man a liar” (Romans 3:4).

Jim Patterson

Editor–Shepherds Voice Magazine

(See also the article British Israelism–A Brief exposure and Refutation)

Britain’s Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt

Introduction

Just over a century ago, in 1908, Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall published a large illustrated book for children called Our Empire Story. Within its covers were tales of ‘India and the greater colonies’, then defined as Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, and the book included evocative colour illustrations by J. R. Skelton. For the children of Empire, for much of the twentieth century, this work provided all that they were ever to know about the history of the world they lived in. Sound, if partial, history, and easy to read, it had a profoundly influential impact.

Henrietta Marshall told the story from an imperial perspective. For the most part, she took no notice of the existence of the various native populations that the empire-builders encountered, though her thumbnail sketches of the inhabitants of southern Africa were clearly designed to summon up a tiny frisson in the mind of her young readers. They were, she wrote, ‘very wild and ignorant … They hated each other and were constantly at war, and some of them, it was said, were cannibals.’

A distinguished popular historian and a woman of her time, Henrietta Marshall was proud of the British Empire. Yet she was also aware of a downside to her tale. ‘The stories are not always bright’, she wrote. ‘How could they be? We have made mistakes, we have been checked here, we have stumbled there. We may own it without shame, perhaps almost without sorrow, and still love our Empire and its builders.’

Such uncritical expressions of affection, seen from the perspective of a century later, are difficult to justify. Descendants of the empire-builders and of their formerly subject peoples now share the small island whose inhabitants once sailed away to change the face of the world. A history of empire today must take account of two imperial traditions, that of the conquerors and that of the conquered. Traditionally, that second tradition has been conspicuous by its absence. One purpose of this book is to provide a balance to the version of events published in older histories of Empire.

The creation of the British Empire caused large portions of the global map to be tinted a rich vermilion. Although not meant that way, the colour turned out to be peculiarly appropriate, for Britain’s Empire was established, and maintained for more than two centuries, through bloodshed, violence, brutality, conquest and war. Not a year went by without the inhabitants of Empire being obliged to suffer for their involuntary participation in the colonial experience. Slavery, famine, prison, battle, murder, extermination—these were their various fates.

Wherever the British sought to plant their flag, they met with opposition. In almost every colony they had to fight their way ashore. While they could sometimes count on a handful of friends and allies, they never arrived as welcome guests, for the expansion of empire was invariably conducted as a military operation. The initial opposition continued off and on, and in varying forms, in almost every colonial territory until independence. To retain control, the British were obliged to establish systems of oppression on a global scale, both brutal and sophisticated. These in turn were to create new outbreaks of revolt.

Yet the subject peoples of Empire did not go quietly into history’s good night. Underneath the veneer of the official record exists another, rather different, story. Year in, year out, there was resistance to conquest, and rebellion against occupation, often followed by mutiny and revolt—by individuals, groups, armies and entire peoples. At one time or another, the British seizure of distant lands was hindered, halted, and even derailed by the vehemence of local opposition.

A high price was paid by the British involved. Settlers, soldiers, convicts—those people who freshly populated the Empire—were often recruited to the imperial cause as a result of the failures of government in the British Isles. These involuntary participants bore the brunt of conquest in faraway continents—death by drowning in ships that never arrived, death by the hands of indigenous peoples who refused to submit, death in foreign battles for which they bore no responsibility, death by cholera and yellow fever (the two great plagues of Empire).

Many of the early settlers and colonists had been forced out of Scotland by the Highland Clearances, in which avaricious landlords replaced peasants with sheep. Many were driven from Ireland in a similar manner, escaping from centuries of continuing oppression and periodic famine. Convicts and political prisoners were sent to far-off gulags for minor infringements of draconian laws. Soldiers and sailors were press-ganged from the ranks of the unemployed.

Then, tragically, and almost overnight, many of the formerly oppressed became themselves, in the colonies, the imperial oppressors. White settlers—in the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Rhodesia and Kenya—simply took over land that was not theirs, often slaughtering, and even purposefully exterminating, the local indigenous population as if they were vermin.

The British Empire was not established, as some of the old histories liked to suggest, in virgin territory. Far from it. In some places that the British seized to create their empire, they encountered resistance from local people who had lived there for centuries or, in some cases, since time began. In other regions, notably at the end of the eighteenth century, lands were wrenched out of the hands of other competing colonial powers that had already begun their self-imposed task of settlement. The British, as a result, were often involved in a three-sided contest. Battles for imperial survival had to be fought both with the native inhabitants and with already existing settlers—usually of French or Dutch origin. This was particularly true in the West Indies in the 1790s, where freed slaves and slaves in revolt, Maroons and Caribs, linked up with French Republicans in attempts to curb the overweening ambition of the British to put the clock back.

None of this has been, during the sixty-year post-colonial period since 1947, the generally accepted view of the Empire in Britain. The British understandably try to forget that their Empire was the fruit of military conquest and of brutal wars involving physical and cultural extermination. Although the Empire itself, at the start of the twenty-first century, has almost ceased to exist, there remains an ineradicable tendency to view the imperial experience through the rose-tinted spectacles of heritage culture.

A self-satisfied and largely hegemonic belief survives in Britain that the Empire was an imaginative, civilising enterprise, reluctantly undertaken, that brought the benefits of modern society to backward peoples. Indeed it is often suggested that the British Empire was something of a model experience, unlike that of the French, the Dutch, the Germans, the Spaniards, the Portuguese—or, of course, the Americans. There is a widespread opinion that the British Empire was obtained and maintained with a minimum degree of force and with maximum cooperation from a grateful indigenous population.

This benign, biscuit-tin view of the past is not an understanding of their history that young people in the territories that once made up the Empire would now recognise. A myriad of revisionist historians have been at work in each individual country producing fresh evidence to suggest that the colonial experience—for those who actually ‘experienced’ it—was just as horrific as the opponents of Empire had always maintained that it was, perhaps more so. New generations have been recovering tales of rebellion, repression and resistance that make nonsense of the accepted imperial version of what went on. Focusing on resistance has been a way of challenging not just the traditional, self-indulgent view of empire, but also the customary depiction of the colonised as victims, lacking in agency or political will.

Many of the rebellions discussed in this book fall into four basic categories. First, as in America, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and parts of Africa, there are the revolts of the indigenous peoples against the British imposition of white settlement and extermination.

Second, there are the revolts of people reluctantly dragooned into the imperial sphere, notably in areas such as India or West Africa, where there was no substantial white settlement and no policy of overt extermination. Here the rebellions often took the straightforward form of resistance to foreign rule.

Third, as in the example of the American colonies, there are the revolts against British rule by the white settlers themselves. These occurred on every continent and were often complicated by a history of previous allegiances—to the French (in Canada and the islands of the Indian Ocean), or to the Dutch (in South Africa though not in Indonesia, where the planned British settlement never materialised).

Fourth, as in the case of the innumerable slave rebellions in the Caribbean and elsewhere, there are the revolts of the workforce in the colonies, slaves in the first instance. Then, when slavery was abolished, cheap labour was provided by indentured labourers brought from overseas, who also resisted. By the twentieth century, many workers had begun to organise themselves with embryonic trade unions, capable of withdrawing their labour and going on strike.

The theme of repression has often been underplayed in traditional accounts, although a few particular instances are customarily highlighted—the slaughter after the Indian Mutiny in 1857, the massacre at Amritsar in 1919, the crushing of the Jamaican rebellion in 1867. These have been unavoidable tales. Yet the sheer scale and continuity of imperial repression over the years has never been properly laid out and documented.

No colony in their Empire gave the British more trouble than the island of Ireland. No subject people proved more rebellious than the Irish. From misty start to unending finish, Irish revolt against colonial rule has been the leitmotif that runs through the entire history of Empire, causing problems in Ireland, in England itself, and in the most distant corners of the British globe.

Endless rebellion in colonial Ireland, followed by fierce repression, famine and economic disaster helped to create an immense Irish diaspora spread over the world, where little Irelands arose to endlessly tease and irritate the British. The British affected to ignore or forget the Irish dimension to their Empire, yet the Irish were always present within it, and wherever they landed and established themselves, they never forgot where they had come from. The memory of past oppression, and the barely suppressed rage at the treatment of previous generations, grew with compound interest over the years.

The British often perceived the Irish as ‘savages’, and they used Ireland as an experimental laboratory for the other parts of their overseas empire, as a place to ship settlers to and from, as well as a crucible for the development of techniques of repression and control. Entire armies were recruited in Ireland, and officers learned their trade in its peat bogs and among its burning cottages. Some of the great names of British military history—from Wellington and Wolseley to Kitchener and Montgomery—were indelibly associated with Ireland. The particular tradition of armed policing, first patented in Ireland in the 1820s, was to become the established pattern for the rest of the Empire.

Irish soldiers—the ‘wild geese’ of legend—fought over the years in almost every European army except the British, serving in France and Spain, in Naples and Austria. Irish Catholics were not permitted officially to serve in the British forces until 1760, when 1,200 men were recruited for service in the marines, although some had infiltrated other regiments before that date. The rules were relaxed during the French and Indian War, and Catholics were more readily recruited.

Protestant landlords remained hostile to this development, arguing that arming such men, who might one day turn against them, was dangerous. They were right to be worried, for a fresh outbreak of violent rebellion occurred in 1761, led by the Whiteboys.

This book highlights the rebellions and resistance of the subject peoples. Implicit in its argument is the belief that Britain’s imperial experience ranks more closely with the exploits of Genghiz Khan or Attila the Hun than with those of Alexander the Great, although these particular historic leaders have themselves been subjected to considerable historical revisionism in recent years. It is suggested here that the rulers of the British Empire will one day be perceived to rank with the dictators of the twentieth century as the authors of crimes against humanity on an infamous scale.

The drive towards the annihilation of dissidents and peoples in twentieth-century Europe certainly had precedents in the nineteenth-century imperial operations in the colonial world, where the elimination of ‘inferior’ peoples was seen by some to be historically inevitable, and where the experience helped in the construction of the racist ideologies that arose subsequently in Europe. Later technologies merely enlarged the scale of what had gone before.

Throughout the period of the British Empire, the British were for the most part loathed and despised by those they colonised. While a thin crust of colonial society in the Empire—princes, bureaucrats, settlers, mercenary soldiers—often gave open support to the British, the majority of the people always held the colonial occupiers in contempt, and they made their views plain whenever the opportunity arose. Resistance, revolt and rebellion were permanent facts of empire, and the imperial power, endlessly challenged, was tireless in its repression. The sullen passivity, for most of the time, of the mass of the population gave a true indication of popular feeling. Individual murder, killings and assassination were sometimes the simplest responses that poor people could summon up to express their resentment of their alien conquerors, yet the long story of Empire is littered with large-scale outbreaks of rage and fury, suppressed with great brutality.

For much of its history, the British Empire was run as a military dictatorship. Colonial governors in the early years were military men who imposed martial law whenever trouble threatened. ‘Special’ courts and courts martial were set up to deal with dissidents, and handed out rough and speedy injustice. Normal judicial procedures were replaced by rule through terror; resistance was crushed, rebellion suffocated.

While many indigenous peoples joined rebellions, others took the imperial shilling. In most of their colonies, the British encountered resistance, but they often had local allies who, for reasons of class or money, or simply with an eye to the main chance, supported the conquering legions. Without these fifth columns the imperial project would never have been possible.

The use of indigenous peoples to fight imperial wars was a significant development in these early years, and became a central element in the future strategy of Europe’s empires. This was as true of India as of the Caribbean and the Americas. Without Indian mercenary soldiers, known as sepoys, Britain could never have conquered and controlled the Indian subcontinent. Clive’s victorious army at Plassey in 1757 was relatively small: 1,000 European troops and 2,000 Indian soldiers. Soon it became necessary to recruit a much larger army of local soldiers to provide protection for the British merchants, traders, and tax collectors moving into the inland markets of Bengal. These mercenaries were subsequently deployed in the 1760s in battles against the Bengali Nawab Mir Kassim.

Indian sepoys played a crucial role in the unfolding history of the Empire, fighting not just in India, but in predatory expeditions sent to Ceylon, to Indonesia, to Burma, to Africa, and eventually to Europe during the great European inter-imperial wars of the twentieth century. They established a pattern for the other mercenary armies of the Empire: the black, originally slave, regiments raised in the West Indies and sent to fight in Africa in the nineteenth century, and to Europe in the twentieth; and the African troops that would fight both in Africa itself, and as far afield as Burma. Without these locally recruited mercenary armies, the expansion and survival of the British Empire would not have been possible.

Yet not every Indian of military age served in the British army. The sepoys who served the British did so because they were paid to do so, and because they were too terrified to withdraw their labour. Britain controlled her mercenary armies with cash and with terror. Much of the early fighting in India in the eighteenth century was devised to secure booty with which to pay the troops. Yet many early campaigns were characterised by sepoy disaffection. Britain’s harsh treatment of sepoy mutineers at Manjee in 1764, with the order that they should be ‘shot from guns’, was a terrible warning to others not to step out of line.

Mutiny, as the British discovered a century later, was a formidable weapon of resistance at the disposal of the soldiers they had trained. Crushing it through ‘cannonading’—standing the condemned prisoner with his shoulders placed against the muzzle of a cannon—was essential to the maintenance of imperial control. This simple threat kept the sepoys in line throughout most of imperial history.

To defend its empire, to construct its rudimentary systems of communication and transport, and to man its plantation economies, the British used forced labour on a gigantic scale. For the first eighty years of the period covered by this book, from the mid-eighteenth century until 1834, the use of non-indigenous black slave labour originally shipped from Africa was the rule. Indigenous manpower in many imperial states was also subjected to slave conditions, dragooned into the imperial armies, or forcibly recruited into road gangs building the primitive communication networks that facilitated the speedy repression of rebellion. When black slavery was abolished in the 1830s, the imperial landowners’ thirst for labour brought a new type of slavery into existence, in which workers from India and China were dragged from their homelands to be employed in distant parts of the world—a phenomenon that soon brought its own contradictions and conflicts.

As with other great imperial constructs, the British Empire involved vast movements of peoples. Armies were redeployed from one part of the world to another; settlers changed continents and hemispheres; prisoners were relocated from country to country; indigenous inhabitants were corralled, driven away into oblivion, or exterminated with smallpox infection (as in North America) or arsenic poisoning (Australia).

There was nothing historically unique about the British Empire. Virtually all European countries with sea coasts and navies had embarked on programmes of expansion in the sixteenth century, trading, fighting and settling in distant parts of the globe. Sometimes, having made some corner of the world their own, they would exchange it for another piece ‘owned’ by another power, and often these exchanges occurred as the byproduct of dynastic marriages. The Spanish, the Portuguese and the Dutch had empires; so too did the French, the Italians, the Germans and the Belgians. World empire, in the sense of a far-flung operation far from home, was a European development that changed the world over four centuries.

While the origins of the British Empire can be traced back to those early years, this book concentrates on the period since the defeats and victories of the 1750s. The Empire had earlier roots, but what is sometimes called ‘the second British Empire’ was basically a creation of the second half of the eighteenth century. The formation of British Canada, the white settlement of Australia, the move into central India, the early experimental incursions into Africa: these were all made possible in the period after Britain and the British colonies in America had gone their separate ways in the wake of the settler war of independence.

At that time, the British Empire was but a few small dots on the map. The colonies established on the Atlantic shores of North America had already been lost, and the tiny English settlements in Canada clung desperately to the eastern seaboard, together with a handful of riverine towns captured from the French. In India, a few coastal cities and their hinterland—Calcutta, Madras, Bombay—were Britain’s only footholds, while the British slave islands in the Caribbean were under constant threat of rebellion. The capture and subjection of Australia, Ceylon, Burma, New Zealand, Tasmania and South Africa lay in the future. So too did the seizure of strategic outposts like Penang and Hong Kong, Singapore and Aden.

The mood in Britain after the loss of the American colonies had hardly been expansionist. William Pitt’s India Act of 1784 famously declared that wars of aggression, and augmentation of territory, were contrary to the interests and injurious to the honour of the British nation. Yet well-meaning phrases formulated in London had no impact on the fresh patterns of domination soon to be established on the ground.

The story of British colonial settlement in America ended for the British in 1781, after two great rebellions, one by the Native Americans, the other by the white settlers. Events in the British Empire in subsequent centuries continued that tradition. Over the next 200 years, not a year went by without major instances of resistance and rebellion occurring somewhere in the Empire. In some years, the rebellions are almost uncountable, reaching a crescendo of resistance that the imperial cohorts were hard-pressed to crush.

While the stories of some individual revolts have often been told, the tale of resistance over two centuries has never before been considered over the wide sweep of Empire. We know about, and are still taught about, the generals and the proconsuls. Shelves groan under their innumerable biographies. In recent decades, we have also been told of the contribution to Empire of the ‘subalterns’ and the British working class. Much less familiar are the stories and the biographies of those who resisted, rebelled, rebelled, and struggled against the Empire’s great military machine.

Over two centuries, this resistance took many forms and had many leaders. Sometimes kings and nobles led the revolts, sometimes priests or slaves. Some have famous names and biographies; others have disappeared almost without trace. Many died violent deaths. Few even have a walk-on part in traditional accounts of Empire. Here, in this book, many of these forgotten peoples are resurrected and given the attention they deserve. For they lie at the heart of Our Empire Story.

Gott, Richard. Britain’s Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt (p. 1-8). Verso Books. Kindle Edition.